George Kulstad, born in Shanghai in 1935, had a tumultuous childhood. His father, a Norwegian sea captain, was held captive by the Japanese, and George and his mother had to make do as best they could during the hard and bleak war years. Unlike many foreigners, the two escaped internment after the Japanese takeover of the international parts of Shanghai in December 1941, but even so, the ensuing years were marked by hardship and deprivation. The Japanese were a constant looming presence. Kulstad has just published his memoirs, A Foreign Kid in World War II Shanghai (read more here.) We asked him what it was like to grow up in wartime Shanghai. Find his fascinating answers below. This is the first of a two-part series.

What motivated you to write the book?

After talking to our children, Erik and Helen, about my family’s three-generation residence in China, I understood that if I did not write now the stories of my life in Shanghai and what I knew of my relatives’ lives in China, this information would be lost to subsequent generations. The memoir took about two years of serious writing to produce, and for a number of years before that I made notes whenever I remembered anything I thought would be of interest. I hope readers will enjoy the memoir and that others might be encouraged to write their own unique stories.

What’s your earliest memory of Shanghai? Was it a happy childhood, at least until 1941?

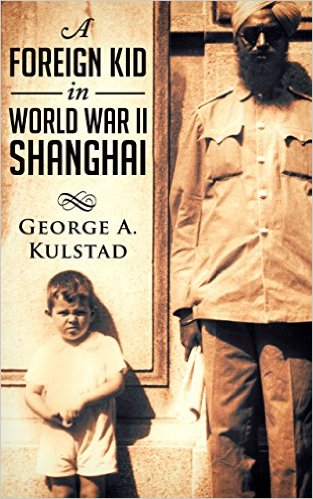

My earliest memory of Shanghai is my being lost on the Bund when I was about 5 years old. I was noticed by a Sikh traffic policeman, probably because I was mimicking his hand signals, and he called his superiors. Two British police inspectors arrived, and they took me to the police station, but I could not provide them my family name or my address or telephone number. Luckily, my mother soon telephoned to report my loss and I was taken home.

Considering all the things that were going on in China in those days, I would say that I had a relatively happy childhood. My first experience of fear was probably when I heard the sound of the Japanese shelling Shanghai, which they did almost simultaneously with their attack on Pearl Harbor. I was not greatly affected by this local outbreak of the war, however, except that it led to the cancellation of the Annual Christmas Bazaar, where I had intended to buy some lead toy soldiers.

Which single recollection from 1941 to 1945 has left the most profound impression?

When I was playing one winter’s day in our living room, I suddenly heard the sound of a heavy slap. I went to the closed French doors, which looked out onto a verandah that faced Quinsan Gardens, a park the size of a block. Through these doors I could see a company of Japanese soldiers standing in formation. One of the soldiers was slumped on the ground. An officer standing in front of him picked him up roughly and slapped him. The soldier slumped down again. This went on several times – each time I could hear the slap. The officer then marched the company out of the park. I could understand Japanese soldiers behaving badly toward the enemy, but to witness brutal behavior toward their own kind was a different matter.

You were not interned after 1941, but many other foreigners were. In your recollection, how much of “the old Shanghai” lived on from 1941 to 1945?

“The old Shanghai” of wild abandon was one I was too young to have experienced, but I recall the occasional comments about it made by my mother and have subsequently read various accounts of it. My recollection of wartime Shanghai is a grey one, marked by shortages of food and fuel, and by oppression, and a sense of being cut off from the rest of the world. We certainly knew about the internment camps, and indeed one of my aunts was taken off to Pootung camp. I later read that some of “the old Shanghai” did live on during that time, as indicated by the number of corrupt officials and military members, from both the Chinese collaborationist government and the Japanese occupiers, who were involved in the black market and were able to lead the “good life” of wine, women, and song.

The Japanese occupation of China is often described as extremely brutal. Was that also your impression then?

The average Chinese had a difficult life in the best of times. With the Japanese occupation, life for most of the Chinese became even more difficult. What I witnessed most often was the fear of Japanese brutality. Whereas in peacetime a crowd of Chinese would quickly gather around any small event on the street, when the Japanese were in power the Chinese would move on and avoid congregating. We all knew of the Kempeitai-operated Bridge House and its sinister reputation. Its location on Szechuan Road was difficult to avoid, but when I had to walk past it I made it a point of using the far side of the street.

What was your view of the Japanese? Were you afraid of them? Were you told to try to stay clear of them?

I was most afraid of Japanese schoolboys. They marched to school in uniform, and in formation, and on the sidewalk, a sidewalk that one quickly learned they owned. I received no parental guidance on my public behavior from my mother, but I quickly learned to avoid trouble. I remember seeing a single drunken Japanese soldier on the sidewalk in front of me and immediately crossing to the other side of the street. I also remember that when I and several Chinese were crossing the Chapoo Road Bridge one day, a red-faced Japanese soldier with his sword drawn and shouting at no one in particular was also crossing the bridge. I and the Chinese all had the common sense to get across the bridge and out of the area as quickly as possible. On another occasion, while I was walking along a sidewalk, an Alsatian dog lunged at me and bit me on the arm when I made the mistake of whistling loudly as I walked past it. Its owner, a Japanese civilian, signaled the dog to call it off me and then, without saying a word to me, walked calmly on with the dog trailing behind him. The behavior of this Japanese and his having a trained dog made me conclude that he was a member of the Kempeitai.

(To be continued.)