How have western views of China’s role in World War Two changed over the past couple of decades? Recently, the Chinese website The Paper published an article on its history channel on this subject, written by Peter Harmsen, author of Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City and Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze. The English version is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Chinese website.

When I was a boy, my favorite possession was a comic book introducing the history of World War Two to young readers by means of simple but evocative drawings and short and clear texts. It was about 100 pages long, and since it was an American comic book, it paid special attention to the US role in the war. What struck me, even back then, was that there was so little about China, barely more than a page. I knew that China was a big country, indeed the most populous country in the world. I felt that there must be much more to the story about China’s part in the war than just this.

As I grew older and started developing a more serious interest in history, the same question kept emerging: why do we know so little about China in the World War Two? Even as China entered into the period of reform and opening up to the outside world and became a more important player on the global scene, its role in the war that shaped the modern age remained virtually uncovered in western historiography, apart from a few scattered monographs, mostly written for an academic audience. To me, it almost added up to a paradox: on the one hand, China is big and receives a lot of attention. On the other hand, World War Two is also the object of significant interest. But the two put together: China in World War Two is a gaping hole in the historical awareness of most people in the west.

Almost every educated person in Europe and North America has heard about the Battle of Britain, the Battle of the Bulge and the Battle of Berlin. Even if most westerners have never read entire books about these events, they have watched films and documentaries. The names of these battles are part of popular culture, and rightly so, since they form milestones in history. Modern Europe as we know it is a child of the World War Two. If the war had turned out differently, Europe would have been a radically different place.

By contrast, almost no westerners have ever heard about the Battle of Taierzhuang, the Battle of Wuhan or the various Battles of Changsha. This is true even for those who pride themselves with having read large numbers of books about World War Two and consider themselves lay experts on that conflict. The Chinese War of Resistance against Japan is a gaping hole in western historiography. It’s a vital missing piece of the giant puzzle of the global conflict that raged from 1937 to 1945 – even though it is impossible to understand the war as a whole without appreciating the role played by China.

For example, the conflict in China in the 1930s forms the backdrop against which the growing rivalry between the United States and Japan unfolded, eventually leading to the attack on Pearl Harbor and full-scale war between the two powers. Ignoring China makes it impossible to understand the Pacific War that broke out in 1941. Similarly, the relatively rapid American advance in the Pacific becomes unintelligible unless it is linked to the large numbers of Japanese troops that were tied down in China, unable to join the defense on the Pacific islands.

These and other facts about the war gradually became clearer to me as I continued my studies in history and the social sciences, and my interest in China’s participation in the war endured as I left Europe following completion of my university education to live and work in Asia. I enrolled as a history student at the Master’s program at National Taiwan University, and while I was there, I tried as much as possible to focus on China during World War Two. For example, I wrote a paper on Deng Xiaoping’s role as a guerrilla leader in the north of the country, using his daughter’s biography as one of my main sources.

Even though back then, in the 1990s, Taiwan was known as the high-tech island, and was very much part of the contemporary world, subtle reminders of the war were all over the place. One of the main boulevards of Taipei was called Roosevelt Road. At the McDonald’s outlet in Ximending in the west of the city you could see the sad contours of veterans trying to make their coffee last while they watched modern life pass by in the streets outside. Sometimes in the papers you would read about some of the giants of the war who were still alive: Song Meiling, or Mme Chiang Kai-shek, in New York, and the “Young Marshal”, Zhang Xueliang, both approaching the age of 100. It was amazing to think that people who had taken part in events before and during the war, at the very highest level of power, were still among us back then.

In the mid-1990s, I also had the opportunity to visit the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea as part of a tour group from Taiwan. Many of the participants were retirees with lots of money and a desire to see the world. Among them was an elderly gentleman who had been forced into the Japanese army during the war, when Taiwan was still a Japanese colony. He explained how he had been stationed in the Pacific and had been forced on the most dangerous duties – storming into enemy fire or stepping across minefields – because, being from Taiwan, his Japanese superiors considered him less valuable. “If your grandfathers had been better shots, I wouldn’t be here today,” the old man told a young American member of the tour group.

The 1990s, of course, was also the decade after the end of the Cold War. From a World War Two historian’s perspective, the most interesting development during those years was the sudden increase in interest in the titanic struggle between Germany and the Soviet Union. Prior to that, the war on the Eastern Front had received only scant attention by western historians, but with the opening of Soviet archives, a whole new chapter in World War Two historiography began.

China, however, remained woefully underrepresented in the growing western literature appearing about the war. Characteristically, the German-American historian Gerhard Weinberg, in his monumental and magisterial volume A World at Arms published in 1995, wrote that “the long war between Japan and China awaits its English-language historian.”[1]

In 1998, I moved from Taiwan to China to work as a foreign correspondent, and I stayed there until 2009. During those 11 years, I witnessed more change compressed into a shorter period of time than I will probably ever see again. But even as I tried to keep track of China’s rapid economic development and modernization, I kept a strong interest in China’s millennia-old history, and to the extent possible I tried to fit articles about history into my daily work as a reporter of current events.

For example, at the 60th anniversary of the victory over Japan in 2005, I had the opportunity to interview a range of veterans and survivors of the war. I talked to a married couple who had fled to Chongqing at the start of the war and had ended up settling down there permanently. My list of interviewees also included a Chinese pilot who had escaped from occupied Hong Kong and had joined the air force in southwest China. Most memorably of all, I visited one of the last surviving veterans of the 1937 battle of Sihang Warehouse.

His name was Yang Yangzheng, and he was 90 years old at the time. I was taken to his modest home on the outskirts of Chongqing by a local city government official who had arranged the visit. Despite his advanced age, he was a big man, and you could imagine he must have been a fearsome fighter in his youth. He had been in one of the iconic battles of the Anti-Japanese War, but he had never bragged about it. Some of his closest neighbors had no idea that they lived next to an actual hero. But the veneration that you could immediately feel among the neighbors once they realized Yang’s past was proof that the war remains an important fact for many Chinese.

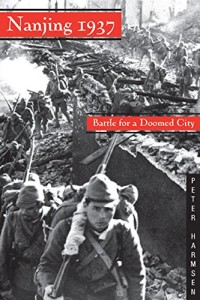

It was about this time that I decided I wanted to write a book about the war in China. It just seemed absurd that such an important story should remain untold and inaccessible to western readers. Initially my intention was to write a volume covering the entire war from 1937 to 1945. It quickly became clear to me that even if it ended up being 500 pages or longer, it would only be able to scratch the surface of all the complexities of this theater of war. Then I considered writing about the first half year of the war, from the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937 until the fall of Nanjing in December of that year. But even that seemed to be a too ambitious undertaking, considering the vastness of the subject, the geographical reach of the events and the variety of actors involved.

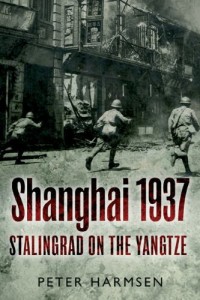

This was why, in the end, I settled for the battle of Shanghai. It seemed a perfect subject. It was clearly delineated both in time and space. It had a well-defined beginning in mid-August 1937 and ended in early November with the withdrawal of the Chinese troops from the city. It was also concentrated in and around the city of Shanghai, so there would be no need for me as an author to be all over the map. Importantly, the battle was full of smaller, dramatic stories of heroism and sacrifice – none more exciting and moving than the struggle of the 800 heroes at Sihang Warehouse.

But what really convinced me that the Shanghai battle was the right material for an entire book was this: it was about a city known to every person on the planet, an icon of cosmopolitanism both in the 1930s and now. Even to those unable to place Shanghai on a map, the mere word rang a bell. And yet, only a tiny number of foreigners – even among the city’s large expat population – were aware that the city had been the scene of a huge, bloody battle at the start of the World War Two. To me it was the entire “China war paradox” in a nutshell: Shanghai was huge and important, just like China as a whole, but its role in the biggest war in history was known only to specialists.

I set about looking for sources for this epic battle, and it immediately became clear to me that there wasn’t too little information, but almost too much. The primary source material was of course mainly to be found in mainland China and Taiwan, but Japan and the United States, too, had important holdings. And then there was one particular place where I would have never thought I would find not just valuable, but actually crucial information: Germany.

It turned out that China was aided in its struggle at Shanghai by a corps of German advisors, most of them veterans of World War One. To learn more about these advisors, I visited the German military archives in the city of Freiburg in the summer of 2011, consulting, among other things, a confidential history of the Shanghai campaign authored by one of the German officers after his return home. It was a strange feeling, sitting in the most German part of Germany, near the Black Forest, studying a battle that had taken place half a world away. It was a reminder that, just as the past events were global, historians’ efforts to untangle these events must be global, too.

Following the publication of my two books on the Shanghai and Nanjing battles[2] I gradually started being contacted by readers who had a personal recollection of events I had written about. For example, I received an email from a senior citizen of the United States, sharing his recollections about life as a young boy in occupied Shanghai. Even though he had been too young to understand everything of what was going on, he had instinctively felt that the Japanese soldiers represented danger, and he had shied away from them.

In addition, this now being the second decade of the 21st century, I felt a growing sense of urgency when it came to interviewing people with a recollection of the war years. Their numbers were getting smaller for every passing year. One of the most interesting conversations was with a Danish businessman who traveled in occupied China in the early 1940s. He told me about arriving in Dalian port on board a ship, watching Japanese soldiers in the harbor area, walking among the cargo: “They were little men with large rifles. They slapped every Chinese who didn’t get out of the way quickly enough. They made a very bad impression.” A few months later, the Dane joined the British Army to fight the Japanese.

With the translation of Shanghai 1937 into Chinese I have had the great luck of attending several conferences in China, convening historians from Chinese universities and from abroad. It has been a truly eye-opening experience to be exposed to the depth and richness of Chinese historical research on that crucial period in history. It is a sign of the maturity of the subject as an academic field of inquiry in China that the topics covered have expanded beyond the core areas of military and political events to also discuss issue areas such as the economic, social and cultural aspects of the war in China.

What strikes me as extremely interesting is the regular presence of Taiwan-based historians at symposiums about the war in mainland China. While scholars from either side of the Taiwan Straits come with different backgrounds, they speak the same language – and by this I mean not just Putonghua, but also the language of the modern scientifically minded and objective historian. With this in common, they now have the opportunity to complement each other and contribute individual pieces to the vast puzzle that is World War Two in China. Significantly, since important wartime archives exist on both sides of the Taiwan Straits, it is a welcome development that they are now able to cooperate and enter into a fruitful dialogue.

At the same time, it is noticeable that western historians also have started participating in events organized in China in greater numbers than before. This is crucial as it will reinforce exchanges between the scholarly communities of different countries. More importantly, it will help position Chinese research into the war in a broader global context and finally, after more than seven decades, give China the place it deserves among the main Allied nations.

Even so, a certain Eurocentric attitude still attaches to most western scholarly approaches to the war in China. Here is one example of that particular phenomenon: without a doubt, the one part of the war in China that has been covered most thoroughly by western historical writers and the western publishing industry is the history of the American Volunteer Group, also known as the “Flying Tigers.” While that story is not unimportant and definitely has its fair share of drama, the amount of attention it has received is out of all proportion with the actual significance of the unit at a time when both sides fielded millions of men in battle.

Perhaps, what is needed is a change of attitude in the west. We have tended to view Chinese history as mainly interesting to the extent that it affects our own history. This is true not just for World War Two historiography, but also more generally for all of Chinese history. For example, western students of the Qing Dynasty have been overwhelmingly interested in the various ways in which the Qing rulers and Qing society interacted with the west in areas stretching from military conflict to trade and technology transfer.

There is a natural human inclination for being most interested in what affects you the most. There is no reason why historians should be above that inclination. Indeed, it is sometimes desirable as historians can contribute more by doing research in areas they are familiar with. Still, there is a risk of becoming too parochial and too convinced that one’s own perspective is the one that matters the most or even the only perspective worth having.

Therefore, it is to be hoped that as western historians become more interested in China’s contribution to the Allied cause in World War Two, they will rise above exclusive concern with the aspects of the war in China that concern their own countries. For example, there does not seem to be a desperate need for more American historians to write yet new books about the “Flying Tigers”. Instead, their time and energy will be much better spent on topics that have hitherto been left under-explored in the west, such as, for example, some of the battles of the later years of the war, such as the battles of Changde or Hengyang.

A western interest in the Chinese war at this level of detail would actually be possible. We have already seen this come about in the studies western historians have undertaken on the German-Soviet war. Two decades after the western academic community started covering various aspects of that great conflict with reference to the newly opened Soviet archives, the field has attained an astonishing level of maturity, and battles that were barely known a generation ago are now the subject of exhaustive studies.[3]

I am confident that in the coming years, as researchers on both sides of the Taiwan Straits achieve even greater levels of cooperation, and as exchanges with their western counterparts multiply, China in World War Two as a field of study in the west will reach a similar level of maturity. It would not surprise me the least if one or two decades from now, we will see in the west the appearance of a two-, three or four-volume work on the battle of Wuhan, for example. Only then will the true story of China’s part in the biggest war in the history of mankind be known to all.

[1] Gerhard Weinberg. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 937.

[2] Peter Harmsen. Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze. Philadelphia and Oxford: Casemate, 2013 and Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City. Philadelphia and Oxford: Casemate, 2015.

[3] A case in point is a massive four-volume history of the 1941 Smolensk battle. David Glantz. Barbarossa Derailed: The Battle for Smolensk 10 July – 10 September 1941. Vol. 1-4. Solihull: Helion & Co. 2010-2015.