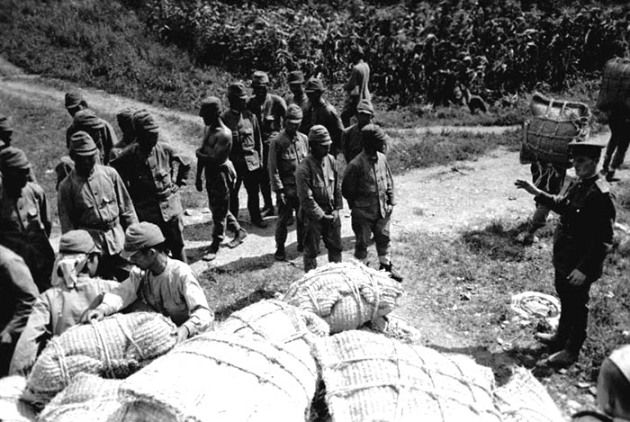

Large numbers of Japanese fell into Soviet hands at the end of World War Two. This happened to both soldiers (see photo above) and civilians. This article is part of a large online project — End of Empire — launched by the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS). The idea is simple: To describe day by day the 100 days immediately after Hiroshima. This article, by Christian Hess, Associate Professor of Modern Chinese History at Sophia University, is reproduced with the kind permission of NIAS. Check out End of Empire here or the Facebook page here. The entire project has now also appeared in book form, see here.

In August 1945, as Japan’s empire abruptly collapsed, over three million civilians along with close to four million military personnel were living outside of Japan’s home islands. The experience of defeat would prove to be as diverse as the empire itself, and the process of protecting and returning this massive population to Japan would prove to be one of the more pressing issues for the victor nations of the Second World War. Returning to Japan and reintegrating into a destroyed, occupied, rapidly reconstituted nation-state would not prove easy.

In the once bustling port city of Dairen, which for 40 years served as a symbol of Japan’s imperial ambition and achievement as ‘Manchuria’s Gateway’, the days immediately following the war brought an eerie calm. The city had largely escaped the bombing that had so devastated cities in Japan, and Darien’s 200,000 Japanese residents, along with 600,000 Chinese, waited to see what the future would hold. That calm was shattered by the outbreak of sporadic fighting between Chinese and Japanese residents, and by the arrival of Soviet military units, which swept through Manchuria and reached Darien on 22 August.

Here, the Soviet military, which would remain in control until 1950, was responsible, along with their counterpart Chinese authorities, for the fate of the Japanese population. In the weeks after their arrival, the less disciplined Soviet troops indiscriminately raped and looted, and Japanese civilians were often the victim of these attacks. Many former Japanese military personnel were sent to Siberia, perhaps 750,000 in all and likely tens of thousands from Darien. Civilians faced an unknown situation, waiting for repatriation ships amidst the fear and anxiety of living in a now Soviet-occupied Chinese city swelling with Japanese refugees from Manchuria. Many of this latter population were born in the colonies, or had spent considerable portions of their lives in colonial cities like Dairen. What would life hold for them in occupied Japan? Could they stay where they had been living and working?

By choice or by order, industrial experts and advisors would in fact stay on in places like Darien for a number of years after the war. Here they not only provided technical assistance, but actively participated in Soviet and Chinese Communist-backed ceremonies and speeches, emphasizing the transformative power of socialism – a potent form of socialist internationalist propaganda which hammered home the theme that through socialism, imperialist enemies could become socialist friends.

The vast majority of Japanese however, would be repatriated to Japan in 1946 and 1947. Life since 1945 had been traumatic for Japanese civilians. Port cities like Darien swelled with refugees from Manchuria, many describing horrific scenes of fleeing both Soviet military violence and vengeance attacks from local Chinese. Many were forced to abandon children and were separated from family and loved ones. As their livelihoods collapsed with the empire’s end, many civilians had little to do but try and survive and wait their turn to board repatriation ships.

Little did they know that this was the beginning of a painful journey back ‘into’ Japanese society. In the reconstitution of Japan after 1945, those who had lived or were born in the colonies were now labeled ‘repatriates’ (hikiagesha), a politicized category that served to mark them out from the rest of the Japanese population. This operated both legally, as official identity documents used this label, but also in terms of social attitudes and behaviour. In the complex process of internalizing defeat, society itself heaped scorn on the repatriates, who came to symbolize betrayal and national shame. Their experiences served as reminders that the process of decolonization would have human costs both in the former colonial territories but also within the homeland itself, a process that would continue for decades after August 1945.